(BĐT) – Although Vietnam has made its initial legislative efforts with the Law on Digital Technology Industry and the pilot regulatory framework for digital assets, this legal corridor remains insufficiently robust to protect investors.

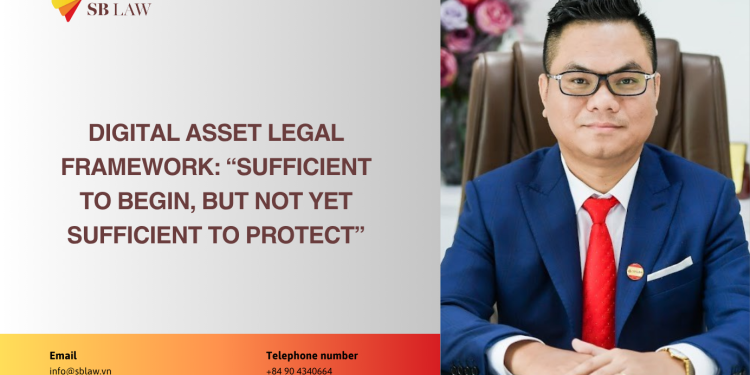

According to Lawyer Nguyen Thanh Ha, Chairman of SB Law, these frameworks merely constitute a preliminary foundation, leaving numerous “legal gaps” that ill-intentioned actors may exploit. This underscores the urgent need for investors to equip themselves with adequate knowledge to safeguard their own interests.

Lawyer Nguyen Thanh Ha, Chairman of SB Law

Legal Ricks and Vulnerabilities in Digital Asset Investment Models

In recent times, public attention has been drawn to the AntEx project, which allegedly exhibited signs of unauthorized capital mobilization and investor fraud under the guise of digital asset investment.

When asked about potential risks arising from current digital asset investment models in Vietnam, Lawyer Ha emphasized that such models present systemic risks stemming from both subjective investor factors and objective market deficiencies.

First, the legal risk remains the most significant. Most fundraising models involving the issuance of tokens, NFTs, or so-called “blockchain projects” are not yet specifically regulated by existing Vietnamese law. The absence of a clear legal framework allows such projects to exploit labels like “new technology” or “decentralized investment” to illegally raise capital beyond the supervision of state authorities. When disputes or acts of misappropriation occur, investors have no effective legal recourse to reclaim their assets or rights.

Second, there is a risk of information opacity and insufficient developer capability. Many projects exist merely on paper, lacking genuine products or technological value, yet are artificially inflated through marketing campaigns and unrealistic profit commitments. Some even adopt Ponzi or disguised multi-level schemes, trapping investors in cycles of “virtual profits”.

Third, technological and cybersecurity risks cannot be underestimated. As most activities take place in the digital environment, the risks of hacking, data theft, or token price manipulation are real and recurring concerns.

Finally, there is a risk derived from investor awareness. A significant number of participants enter the market driven by a “fear of missing out” (FOMO), lacking fundamental understanding of blockchain mechanisms, tokenomics, or smart contracts. Without a solid knowledge base, such investors become easy targets for sophisticated fraud schemes.

Digital asset investment is undoubtedly a sector with potential; however, in the absence of a comprehensive legal and supervisory framework, the risks of capital loss, erosion of market trust, and financial insecurity remain alarming.

Question:

Do the existing pilot legal frameworks — namely Law No. 71/2025/QH15, Resolution No. 05/2025/NQ-CP, and the Hanoi Convention — provide adequate protection for investors and effectively mitigate risks?

Answer:

The enactment of Law No. 71/2025/QH15, together with Resolution No. 05/2025/NQ-CP and the Hanoi Convention, represents commendable progress. These instruments demonstrate Vietnam’s proactive and visionary approach in shaping the legal infrastructure for digital asset technologies — a nascent and dynamic yet highly risky domain.

However, it is premature to conclude that the current framework is sufficiently strong to fully protect investors or prevent systemic risks.

First, Law No. 71/2025/QH15 – the Law on Digital Technology Industry serves primarily as a framework statute, establishing broad management principles and development orientations for the digital technology sector. It has yet to provide detailed regulations governing the issuance, trading, custody, and protection of digital or tokenized assets. While the Law encourages experimentation within regulatory sandboxes and defines the general rights and obligations of digital platform participants, it lacks specific sanctions for acts such as illegal fundraising, fraud, price manipulation, or digital asset misappropriation. Consequently, the Law’s deterrent effect and investor protection capacity remain limited — particularly given the increasingly sophisticated and transnational nature of cybercrime and digital fraud.

Second, Resolution No. 05/2025/NQ-CP on the pilot operation of the digital asset market offers a flexible mechanism enabling the State to balance regulatory oversight with controlled experimentation. This is a sound approach since blockchain technology and digital assets require a testing environment to mature.

Nonetheless, the scope of the pilot remains narrow, restricted to a limited number of licensed enterprises and organizations. The vast majority of token issuance, fundraising, and trading activities occur outside the pilot framework—effectively beyond any safe regulatory boundary. This creates a substantial grey area, where most violations and investor losses originate, due to the absence of timely monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. In addition, information disclosure requirements under the Resolution are still rather general and lack enforceable standards.

Third, the Hanoi Convention marks a breakthrough in cross-border cooperation, particularly in data sharing, tracing crypto asset flows, and combating cybercrime. However, its practical effectiveness heavily depends on each signatory nation’s domestic incorporation and enforcement capacity. Investigating and freezing digital assets require advanced blockchain forensic technology, robust data infrastructure, and stringent legal procedures — areas where Vietnam is still building capacity. Thus, while the Convention establishes an international coordination framework, actual recovery of digital assets and investor compensation in Vietnam remains challenging and will require time before the Convention yields tangible results.

Question:

You have just analyzed that the current legal framework is merely an initial step. In your opinion, what specific steps should Vietnam prioritize to build a comprehensive and effective legal corridor to protect investors?

Answer:

From an overall perspective, it can be said that the current legal framework is “sufficient to begin,” but not yet “sufficient to ensure comprehensive protection.” To make these legal instruments truly effective, Vietnam needs to promptly promulgate detailed decrees and circulars providing specific guidance. These should clearly define:

-

Standards for classifying digital assets (such as utility tokens, security tokens, and stablecoins);

-

Conditions for issuance and trading;

-

Requirements for technological audits, system security, and financial transparency;

-

Mechanisms for custody, insurance, and investor compensation in the event of platform or project collapse; and

-

Strict sanctions against acts of unlawful fundraising or digital asset fraud.

In addition, it is necessary to establish a National Center for Blockchain Monitoring and Analysis to enhance the State’s capacity in investigating and tracing digital asset flows. At the same time, Vietnam should create a Digital Asset Investor Protection Fund, financed by contributions from licensed exchanges and issuers, to provide remedial support in case of risks or losses.

Furthermore, investor education and public awareness campaigns must be strengthened, as in practice, many participants still lack sufficient understanding of blockchain mechanisms, tokenomics, and the associated legal risks.

In conclusion, the current legal framework represents a positive signal, laying the groundwork for the transparent and sustainable development of Vietnam’s digital asset market. However, to assert that the system is “strong enough to protect investors” will require more time, technical detail, and determined enforcement efforts. The safety of investors depends not only on written regulations, but also on actual management capacity, inter-agency coordination, and the overall compliance culture of the market.

Consultation: TMT Law Services